Contributions to family holdings: current situation and unresolved issues

Family holdings have become one of the most effective tools for organising and protecting the assets of family businesses. This type of structure not only helps maintain market competitiveness but also ensures business continuity across generations, offering a more orderly and efficient framework for managing a corporate group.

To achieve this objective, the creation of family holdings allows for the centralisation of management and for such entities to act as the parent company of the various subsidiaries within the group.

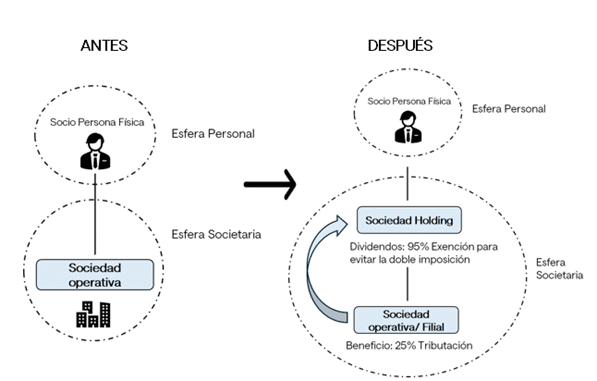

In simple and schematic terms, this structure enables the following corporate configuration to be achieved:

This organisational form makes it possible, among other things, to centralise the management of shareholdings, unify cash flows generated by different operating companies, facilitate strategic decision-making, plan new investments, and, above all, organise business succession by avoiding the fragmentation of ownership that typically occurs when new generations enter the company.

With the aim of encouraging their creation, the legislature has established a specific tax regime for such operations: the tax neutrality regime for mergers, demergers, contributions of assets and share exchanges (commonly referred to as the FEAC regime), currently governed by Articles 76 et seq. of Law 27/2014 of 27 November on Corporation Tax (“LIS”), and by Articles 48 and 49 of Royal Decree 634/2015 of 10 July, which approved the Regulation on Corporation Tax (“RIS”).

This regime allows the deferral of taxation on the income realised as a result of the transaction, provided that valid economic reasons exist and the purpose is not tax fraud or tax evasion.

However, in recent years the Tax Inspectorate has increasingly challenged the application of this regime to contributions made to family holdings, arguing that in many cases such transactions lack sufficient economic justification and pursue only the achievement of tax advantages.

Unsurprisingly, this situation has given rise to significant litigation involving the Directorate-General for Taxation (DGT), the Central Economic-Administrative Court (TEAC), the National High Court, and, more recently, the Supreme Court.

The Tax Administration’s position on family holdings

The Tax Administration’s usual practice has been to consider that contributions of shareholdings to family holdings by individuals were made solely for the purpose of avoiding taxation under Personal Income Tax (IRPF).

In most tax audits, the Tax Inspectorate identifies two principal tax advantages:

- The non-taxation of dividends distributed by the operating companies to the family holdings, as the latter applies the double taxation exemption under Article 21 of the LIS.

- The deferral of taxation on the latent capital gains inherent in the contributed shareholdings.

Based on this reasoning, the Inspectorate’s usual practice has been to deny the neutrality regime and require full taxation of the capital gain in the year the contribution was made — even where no dividends were distributed and no sale of shareholdings occurred.

The DGT and family holdings: a significant nuance

In 2023, the Directorate-General for Taxation (DGT), through Binding Ruling V2214-23, introduced a significant change of approach.

It acknowledged that in cases of fraud or tax evasion, the Tax Administration should not eliminate the entire tax deferral, but should instead limit the adjustment solely to the specific advantage obtained.

In practical terms, this meant focusing the correction on dividends distributed from profits generated prior to the contribution, rather than taxing the entire capital gain from the outset.

The TEAC’s position on family holdings

The Central Economic-Administrative Court (TEAC) took the matter further in several resolutions issued between 2024 and 2025.

While agreeing with the Tax Inspectorate that the special regime should be denied in the absence of valid economic reasons, the TEAC introduced a more balanced view of how the tax adjustment should be carried out:

- Gradual taxation. The capital gain should not be fully recognised in the year of the contribution but only as dividends are distributed from profits generated prior to the transaction.

- Defining the abuse. The abusive tax advantage is deemed to relate solely to those pre-existing reserves that could have benefited from the 95% exemption under Article 21 of the LIS. Expected future profits or unrealised gains not linked to specific assets are not included.

- Application of a “FIFO-like” principle. This means that the first dividends distributed are automatically attributed to earlier profits, even if the shareholders’ resolution states otherwise or if the holding company accounts for them as financial income rather than as a reduction in the carrying value of the investment.

- Coordination between legal frameworks. This approach seeks to harmonise Article 37.1(d) of the IRPF Law, which regulates deferred payment operations, with Article 89.2 of the LIS, which provides that the tax adjustment should remove only the specific fiscal advantage identified.

Critical assessment of the TEAC’s approach

In our view, the TEAC’s definition of abuse is open to question, since considering the exemption under Article 21 of the LIS as a “tax advantage” disregards the full cycle of taxation of the income in question — that is, from its generation by the subsidiary company through to its inclusion in the individual shareholder’s personal estate.

If the entire tax cycle is not considered, the comparison is made between economically non-equivalent situations, and thus it becomes impossible to assess whether they have equivalent or comparable economic effects.

When examining the full taxation process, the following occurs:

- When the subsidiary distributes a dividend to its parent (the holding company), and the latter applies the general corporate tax rate, it bears an effective tax burden of 1.25% (since 95% of the income is exempt).

- Subsequently, for comparability, that dividend must ultimately be distributed by the holding company to its individual shareholders, triggering personal income tax at rates between 19% and 30%.

Therefore, when the entire taxation chain is considered, the overall tax burden on such income increases — no genuine tax saving arises.

Of course, if that income remains within the holding company and is not distributed to the individual shareholders, the personal income tax is merely deferred, not eliminated. The Tax Agency does not lose its ability to tax the income; taxation is simply postponed until it reaches the individual shareholder level.

In our opinion, regularising this scenario does not serve to protect the public revenue. At best, it merely brings forward tax collection.

Moreover, this effect would occur in all contribution operations made by individuals applying this tax deferral regime. Consequently, if such deferral were deemed an abusive tax advantage prohibited by law, the regime would never apply to any contribution involving pre-existing reserves — since those reserves would always be subject to taxation (especially under the aforementioned “FIFO” rule).

For this reason, we believe that the exemption cannot be regarded as an abusive tax benefit requiring disapplication.

The Supreme Court will have the final word

Nevertheless, the debate remains unresolved.

In March 2025, the Supreme Court admitted an appeal in cassation on grounds of objective cassational interest. The key issues it will need to decide include:

- Whether the anti-abuse clause permits the application of a principle of proportionality, such that the adjustment does not automatically entail total loss of the tax deferral.

- Whether the Tax Administration may limit its rejection to part of the benefits under the regime, rather than disallowing it in its entirety.

- Whether the dividend exemption under Article 21 of the LIS should be considered an abusive “tax advantage” or, conversely, a legitimate mechanism to prevent double taxation.

The forthcoming judgment will be highly significant, as it will establish a binding precedent for both the Tax Administration and lower courts, hopefully providing greater legal certainty for family-owned enterprises.

Outstanding controversial issues

In the meantime, several practical matters remain unresolved:

- Subsequent transactions. There is still no judicial guidance on how to avoid double taxation in subsequent operations (e.g. capital reductions or distributions of share premium). However, in a December 2024 ruling, the TEAC held that double taxation should be corrected by increasing the acquisition value of the contributed shares/holdings in the hands of the individual contributor. This means that double taxation would only be avoided upon disposal of the holding company (as its acquisition cost would be higher), but not in dividend distributions to individual shareholders — with all the negative effects that entails.

- Taxation at the holding company level. It must not be overlooked that dividends received by the holding company have already borne 5% tax, and there is as yet no pronouncement on how to mitigate this effect when an adjustment is made against the individual contributors.

- Prescription of the transaction. Questions also remain regarding what happens when dividends are distributed years after the contribution, and whether this affects the limitation period of the Administration’s enforcement powers. There is currently no ruling clarifying the interplay between the powers of verification and investigation under Article 115.2 of Law 58/2003 of 17 December, the General Tax Law, and corporate restructuring operations.

Conclusions

The taxation of contributions to family holdings is currently a hot topic. The Tax Administration has sought to adopt a very restrictive approach, whereas both the DGT and the TEAC have attempted to introduce more balanced criteria for regularisation — although, in our view, such criteria remain open to debate.

In light of all the above and pending the Supreme Court’s decision, our recommendation to family-owned businesses is clear: carefully document the economic and management reasons justifying the creation of family holdings. Doing so will strengthen the robustness of these transactions in the event of a subsequent tax audit.

At Devesa, we have a team of tax advisers specialising in the formation of family holdings and corporate restructuring operations.

If you require further information, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Do you need legal advice? Access to our area related to family holdings: