International tax transparency: an increasingly relevant regime in the face of growing profit relocation

In the current environment where business groups can operate simultaneously in multiple jurisdictions, structuring their investments in many cases through holding entities located abroad, the correct application of international taxation has become a critical factor for the prevention of unassessed risks.

A mechanism that is currently unfamiliar to Spanish taxpayers, although with a significant potential impact, is the international tax transparency regime, also known as CFC rules (Controlled Foreign Companies).

This regime has been present in Spanish legislation for over twenty-five years; however, it has gained particular prominence in recent years due, among other things, to the increasing oversight by tax authorities of base erosion, the use of structures lacking sufficient economic substance, and the relocation of profits to low- or no-tax companies. Tax authorities are increasingly intensifying their scrutiny of international structures, particularly those lacking a sufficient and appropriate physical presence of personnel and resources.

What does international tax transparency consist of and when does it apply?

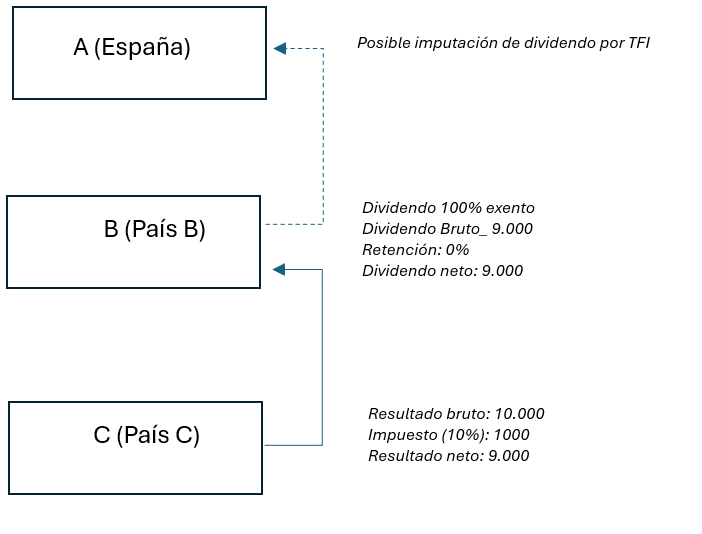

This regime basically establishes that certain income obtained by non-resident entities must be directly imputed to the tax base of the resident entity that controls them, even if they have not been distributed to it and, legally, are income attributable to the entity that obtains them.

Article 100 of the Corporate Income Tax Law establishes the conditions that must be met for this mandatory allocation to take effect. These can be summarized in three essential points:

1.1. CONTROL

There must be significant control by the resident entity over the non-resident entity. According to the Spanish Corporate Income Tax Law (LIS), this requirement is considered met when the Spanish entity, alone or together with related parties, holds at least 50% ownership, voting rights, or profits in the foreign entity.

The concept of control can be broader than the purely commercial one, so it is common for groups that do not believe they are within the scope of the aforementioned Article 100 IS, to actually be so, after a detailed analysis.

1.2. LOW TAXATION

Low taxation is considered to exist when the foreign entity pays a tax of a similar nature to corporate income tax that is less than 75% of what it would have paid in Spain.

This seemingly simple requirement has been the subject of intense interpretive debate, especially regarding exempt income. As we will see, the Tax Administration has recently had to clarify how this criterion should be applied.

1.3. OBTAINING PASSIVE INCOME

Article 100 distinguishes two scenarios in this regard:

- Insufficient personal and material resources (art. 100.2.LIS): in this case, all income would be attributed to the foreign entity.

- Obtaining specific passive income (art. 100.3. LIS): detailed in article 100.3. LIS, mainly dividends, interest, royalties, real estate income, capital gains from financial and insurance activities, related-party transactions without added value, etc.

Historically, the inability to consider certain income exempt easily triggered the application of the regime, even in the case of operations whose purpose was legitimate.

Redefining passive income in the European context

The impact of European Union law and community jurisprudence led to considering dividends and capital gains as passive income, even if they benefit from the exemption of dividends and capital gains established in Spanish regulations (art. 21 LIS).

The tax authorities did not consider these incomes as passive when they were exempt, which greatly minimized the scope of tax transparency. With this new interpretation, practically all corporate income from international subsidiaries came to fit conceptually under Article 100.3 (cases of passive income to be attributed to the shareholder in cases of international tax transparency).

Differential taxation problem: the famous 1.25%

Following the 2021 reform of the Corporate Income Tax Law, income from dividends and capital gains that were previously exempt, maintains a non-deductible amount of 5% (as management expenses), which is equivalent to an effective taxation in Spain of 1.25% on said income.

Many other jurisdictions, however, apply a full 100% exemption without counting that residual non-deductible expense (5%).

This raises the question of whether a foreign company claiming a full exemption should be considered “low-taxed,” since it pays less tax than its Spanish equivalent. In theory, the CFC regime would be triggered, resulting in double taxation of the non-exempt 5%.

The Directorate General of Taxes recently clarified (V2138-24) that this difference should not be taken into account. In other words, if a dividend or capital gain is exempt in the foreign entity, and would have been exempt in Spain except for the 5% management fees, there is no low taxation, even if the remaining 1.25% is taxed in Spain, and therefore the transparency regime does not apply.

This administrative criterion provides legal certainty and prevents the automatic and distorted application of the CFC regime in legitimate international structures.

But be careful, if the foreign entity applies an exemption that would not be applicable in Spain, or if it classifies income as exempt that would have been fully taxable in Spain, there would be low taxation in the intermediary company, activating the transparency regime.

The importance of economic substance in international tax transparency

Article 100.2 of the LIS is clear: if the foreign entity does not have the appropriate material and personal resources to carry out its activity, all the income obtained by the entity is imputed, regardless of its nature.

This approach reflects the growing importance of the concept of economic substance, reinforced by international initiatives (BEPS anti-erosion standards, Pillar 2, ATAD anti-avoidance directive) and which seeks to avoid merely instrumental structures.

Today, using companies without employees, without real decisions and without verifiable economic activity, solely to channel profits, constitutes a real tax risk that can trigger unpleasant consequences, such as imputations of income and taxation in Spain, transfer pricing adjustments, questioning of tax residency, or even declarations of simulation or conflict in the application of the rule, with the consequent regularizations and sanctions.

The objective of international tax transparency is not to penalize internationalization, but to prevent the artificial generation of passive income in low-tax territories.

Therefore, it is critical to periodically review international structures, in the sense of:

- Analyze the true substance of related foreign entities

- Document the Group’s operations very well, especially strategic decisions and descriptions of key functions and their location.

- Reconciling the structure with BEPS criteria (base erosion and profit shifting rules), and with OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) standards

- Monitor compliance with the requirements of the aforementioned Article 100 LIS.

Conclusion: The importance of international tax transparency in international expansion strategies and reorganization of multinational groups

In the current context, international tax transparency is no longer a marginal aspect of Spanish legislation: it is an increasingly operational tool, aligned with the global trend of combating the artificial relocation of profits. Its proper application and prevention are essential in any international expansion strategy or reorganization of multinational groups.

The key lies in understanding the nature of the income, identifying the value chain and the location of key functions in international groups, demonstrating the economic substance of the group entities, and anticipating the tax consequences for the Spanish partner.

Do you need advice? Access our areas related to international tax transparency:

Tax Advice